Xpat.gr visited Vergina, ancient Aigai—the royal metropolis of the Macedonians—

to explore the Museum of the Royal Tombs

and the New Central Museum Building of the Polycentric Museum of Aigai,

a journey we now share with you!

Table of Contents

Click any item below to jump to the relevant section of our museum journey.

- Our Museum Journey

- The Archaeological Site of Aigai

- The Great Tumulus (Megali Toumba) – Excavations under Manolis Andronikos

- 1. Museum of the Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures

- 2. Central Museum Building of Aigai

Our Museum Journey

This article takes you inside two important museums in Vergina: the Museum of the Royal Tombs and the New Central Museum Building—both integral parts of the Polycentric Museum of Aigai.

First Stop: The Museum of the Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures

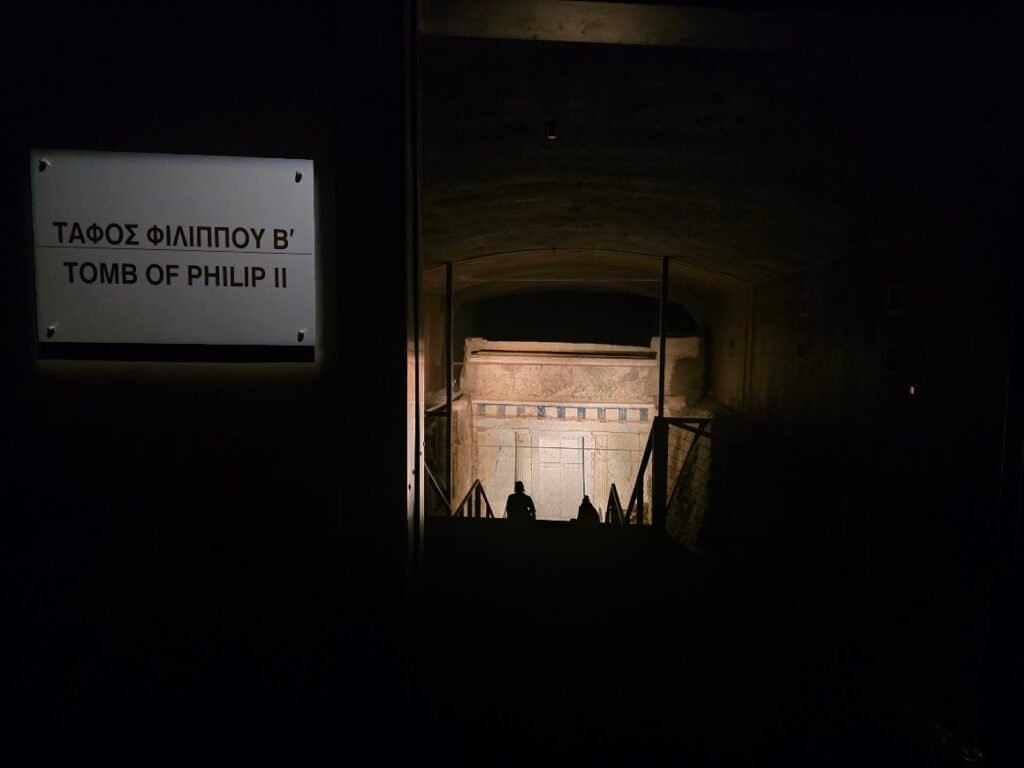

We begin our journey at the Museum of the Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures, located beneath the reconstructed Great Tumulus. Visitors step into a low-lit, subterranean space where the royal graves are preserved in situ, including the tomb of King Philip II.

Moving below ground level, one encounters gold wreaths, ceremonial armour, and ritual objects, all displayed with deliberate restraint, allowing the gravity of the setting to speak for itself. The museum immerses visitors in the solemn world of Macedonian burial practices while revealing the exceptional artistic mastery of the era.

Second Stop: The New Central Museum Building

A short distance of 1.7 kilometres leads to a striking contrast: the New Central Museum Building, constructed of luminous white stone and flooded with natural light. Designed as the symbolic gateway to the archaeological site of Aigai, this contemporary museum places the tombs and treasures within a broader historical framework.

Here, the story expands beyond kings and burial ritual to explore the institutions, daily life, and cultural foundations of Ancient Macedonia, tracing the kingdom’s rise and its lasting influence on the wider Hellenistic world. History unfolds in light-filled galleries that feel analytical, open, and alive.

Together, these two museums offer a rare and balanced encounter with the past—one intimate and contemplative, the other expansive and explanatory. For those living in Greece or visiting for the first time, Vergina is more than an archaeological site: it is a reminder that some of the most far-reaching chapters of global history began in landscapes that still feel quiet, human, and deeply rooted in the land.

To prepare you for your visit—and before showcasing the remarkable museum exhibits—we will briefly explain the layout of Aigai’s archaeological sites and the position of the Royal Tombs beneath the Great Tumulus. This background allows visitors to fully appreciate the museums: the Museum of the Royal Tombs immerses you in the treasures uncovered within the Great Tumulus itself, revealing the artistry, rituals, and lives of Macedonia’s royal family. The New Central Museum Building then broadens the perspective, showcasing finds from across the entire archaeological site and offering a richer view of daily life, culture, and society in ancient Aigai.

The Archaeological Site of Aigai

The archaeological site of Aigai, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996, provides essential context for the treasures displayed in its museums. Among its most impressive remains is the monumental palace, dated to around 340 BCE, which ranks among the grandest buildings of the classical period with expansive courtyards and intricate mosaics. Nearby stands the theatre where Philip II was assassinated in 336 BCE during the wedding of his daughter Cleopatra of Macedon to Alexander I of Epirus; the ceremony, attended by many Greek dignitaries, turned tragic when Philip—appearing unprotected to seem approachable—was fatally stabbed by Pausanias of Orestis, a member of his bodyguard.

The site also preserves sacred precincts devoted to Eukleia and the Mother of the Gods, ancient fortification walls, and a vast royal necropolis: more than 500 tumuli (burial mounds) mark the cemetery and contain elite graves dating from the 11th to the 2nd centuries BCE. While the outdoor ruins convey Aigai’s scale and grandeur, the story of the ancient capital comes fully to life inside the museums, where the artifacts from these monumental contexts are exhibited and interpreted.

Aerial view of the archaeological site of Aigai (UNESCO World Heritage Site), revealing the outline of the palace and theatre — the very landscape where Macedonia’s royal dynasty once shaped history.

The Great Tumulus (Megali Toumba) – Excavations under Manolis Andronikos

The story of the excavation of Aigai’s royal tombs began in 1861, when French archaeologists Léon Heuzey and Henri Daumet uncovered the first Macedonian tomb — one of more than 540 burials that would subsequently be documented across the city’s necropolis, in use from the Early Iron Age to the Roman era. But it would take more than a century for the Great Tumulus to reveal its secrets.

Modern excavations reached a turning point between 1976 and 1980, under the renowned Greek archaeologist Manolis Andronikos (1919–1992), whose decades-long persistence would forever reshape our understanding of Macedonia’s royal past.

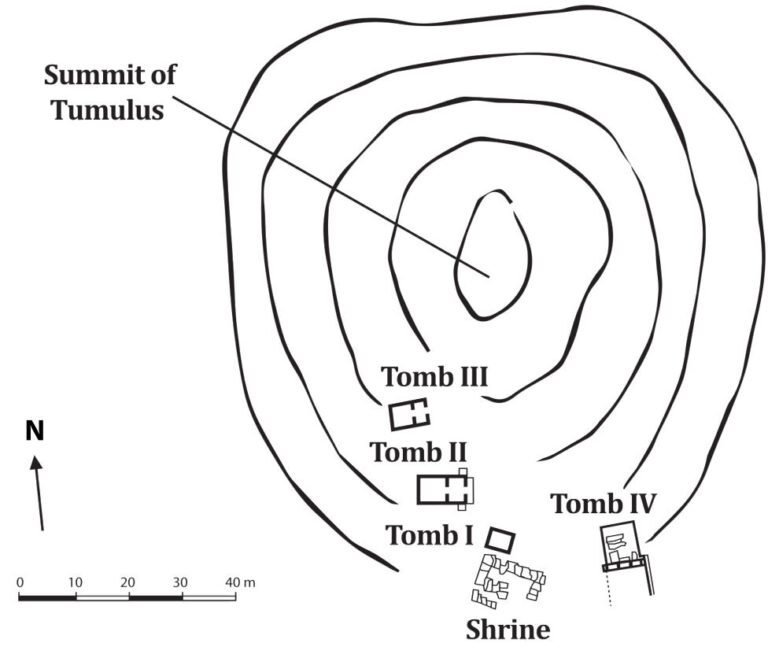

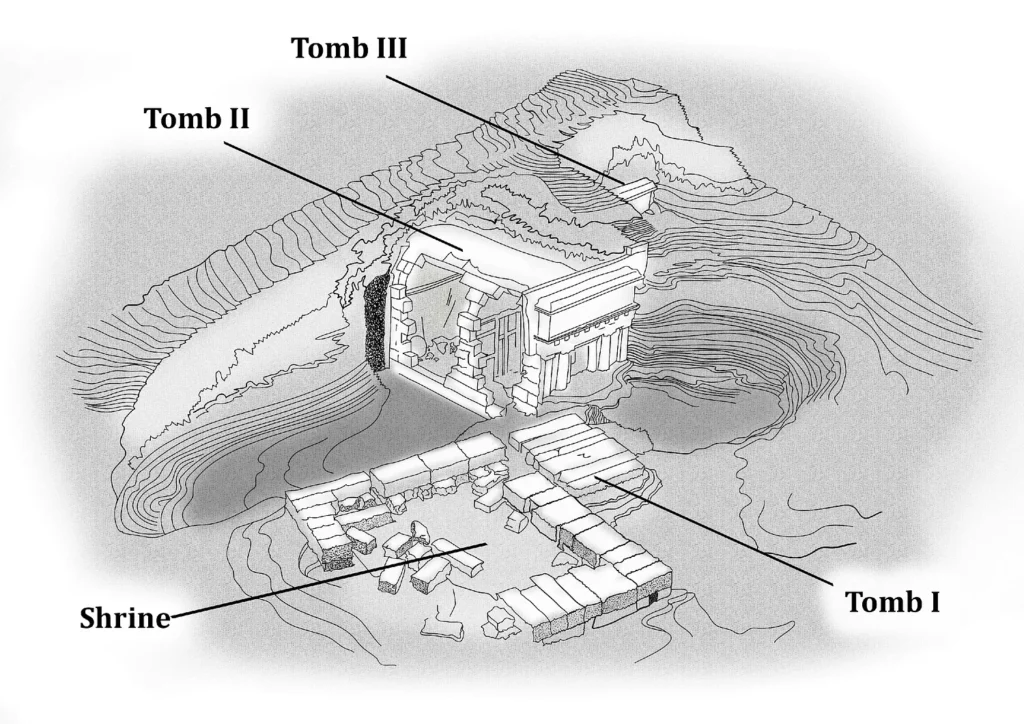

On 8 November 1977, Andronikos opened the Great Tumulus (Megali Toumba) and entered Tomb II, the only unlooted royal Macedonian tomb ever discovered, which he attributed to Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. Inside lay golden larnakes, ivory reliefs, and ceremonial armour, celebrated as “the find of the century.” That same year, he also uncovered the box-shaped Tomb of Persephone (Tomb I). In 1978, the unplundered Tomb of the Prince (Tomb III), believed to hold Alexander IV, was discovered. The remarkable ensemble of monuments at the Great Tumulus was completed by two additional structures, heavily damaged but historically significant. Adjacent to the Tomb of Persephone, the foundations of a heroon—a small stone above-ground structure honoring the deceased of the neighboring royal tomb, Philip II—were revealed. A few meters from these main burial monuments, in 1980, the remains of a third Macedonian tomb, which had suffered extensive destruction, were excavated. This tomb is known as the Tomb With the Free-Standing Columns (Tomb IV), dating to around 300 BCE.

“I can clearly recall the reaction I felt as I said to myself: ‘If the suspicion I had — that the tomb belongs to Philip — is true, and the golden larnax confirms this suspicion, then I was holding in my hands the larnax containing his bones. It is an incredible and terrifying thought, one that seems completely unreal.’ I believe I have never experienced such a thrill in my life, nor will I ever again.”

Tomb Ι: Tomb of Persephone, Tomb II: Tomb of Philip II,

Tomb III:Tomb of Alexander IV — “Tomb of the Prince”,

Tomb IV: Tomb with the Free Columns

Tomb Ι: Tomb of Persephone

Tomb II: Tomb of Philip II

Tomb III: Tomb of Alexander IV — “Tomb of the Prince”

1. Museum of the Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures

The Exterior

It is widely acknowledged that the excavation of earthen structures often entails an element of destruction; thus, the original Great Tumulus no longer exists in its original form. Instead, the Museum of the Royal Tombs—Display of Treasures has been thoughtfully constructed to simulate the Great Tumulus, serving as a protective shelter that preserves the authentic royal tombs within, which have undergone only minimal modern interventions to ensure their continued stability. This tumulus-shaped structure harmonizes with the ancient monuments it encases, showcasing both architectural ingenuity and a profound respect for history.

From the outside, the museum presents a serene grassy mound, an intentional design that invites curiosity. Since its opening in 1993, the museum allows visitors to traverse the tumulus much like the archaeologists who first unearthed these buried treasures.

Museum of the Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures: Key Monuments of the Great Tumulus

Tomb I (Tomb of Persephone): Though looted, this tomb is renowned for its majestic fresco that adorns the walls of the burial chamber, depicting the abduction of Persephone by Hades. It serves as a vivid expression of ancient mythology and artistry.

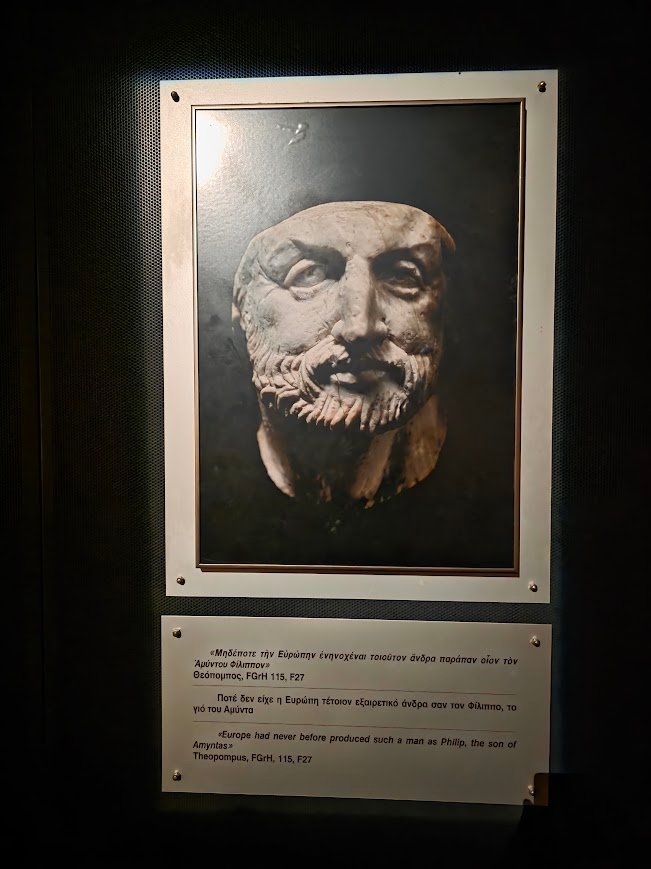

Tomb II (Tomb of Philip II): The most famous tomb, identified by many archaeologists as belonging to King Philip II, father of Alexander the Great. It was unlooted and contained rich grave goods, including the golden larnax with the “Star of Vergina” (sixteen-pointed) holding the bones of the deceased, an elaborate golden oak wreath, the king’s armor, and various silver and gold vessels, alongside exquisitely carved ivory miniatures.

Tomb III (Tomb of Alexander IV — “Tomb of the Prince”): Believed to be the resting place of Alexander IV, the son of Alexander the Great and Roxana, this unlooted tomb features grave goods such as a silver hydria containing the remains of the deceased and a ceremonial golden wreath.

Tomb IV (Tomb With the Free-Standing Columns): Found in a heavily damaged state, this tomb dates back to around 300 BCE .

Heroon (Hero Shrine): Located near the tombs, this monumental structure is dedicated to the worship of deceased kings. Unfortunately, it was also found looted, reflecting the turbulent history that has surrounded these ancient treasures.

The Interior

Funerary Stelai • Tomb with the Free-Standing Columns (Tomb IV) • Tomb of Persephone (Tomb I)

As you descend the gently sloping path into the depths of the museum, a profound shift in ambiance occurs—a blend of mysticism and reverence surrounds you. The air is thick with an ancient silence, as if the very stones themselves resonate with the weight of history and echoes of untold stories from a civilization that once thrived here.

Inside, dim lighting and cool air envelop guests, safeguarding the delicate frescoes, gold and ivory ornaments, and intricate metalwork housed within. This immersive environment guides visitors through a landscape rich with ancient rituals, enabling them to connect with the grandeur of a bygone civilization.

As your eyes adjust to the gentle dimness, the exhibits gradually unveil their secrets. You find yourself standing before imposing Funerary Stelai—or tombstones—adorned with intricate carvings that tell stories from the graves of ordinary Macedonians.

As you move deeper into the exhibit, you come across the remains of the Macedonian Tomb With the Free-Standing Columns (Tomb IV), a remarkable monument dating back to the 3rd century BCΕ, situated at the edge of the Great Tumulus. Nearby, you will find the Heroon, a structure dedicated to the cult of the eminent dead, and notably the only monument in the museum that stands above ground.

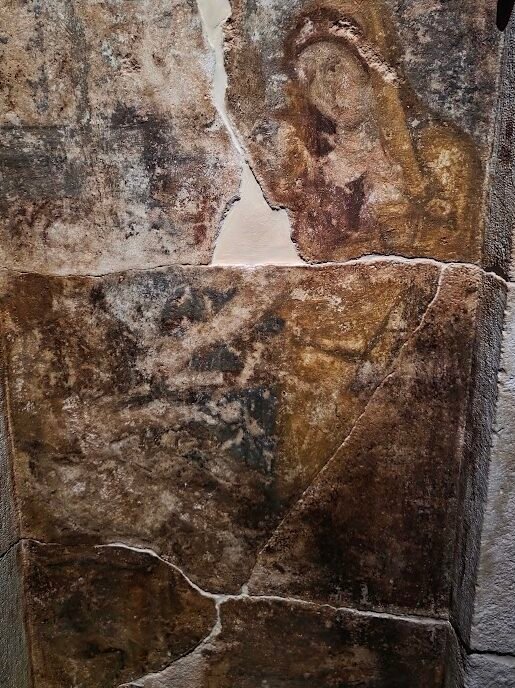

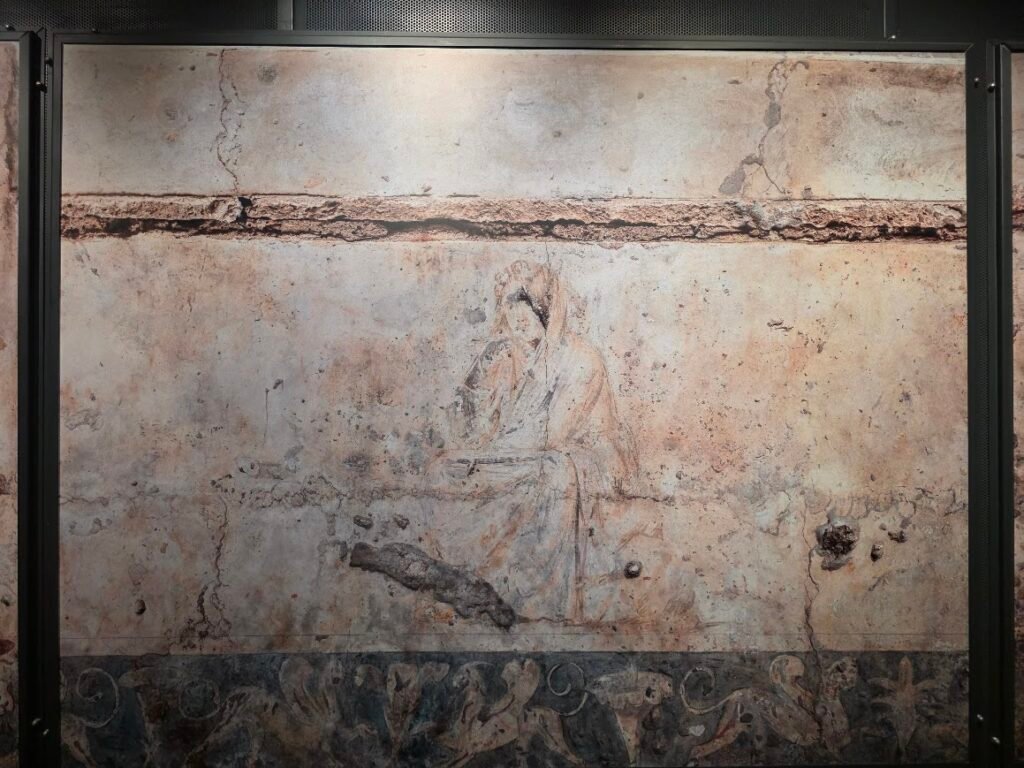

Behind the Heroon, a striking and faithful replica of the fresco that decorates the antechamber of Tomb I (the Tomb of Persephone ), invites you to witness a defining moment in mythology with its illustration of the Abduction of Persephone by Hades. Tomb I is an unfortunately plundered cist grave that is part of the royal burial complex of the Macedonian kings. Although there has been recent debate regarding the identity of its occupant, it is widely believed to be the tomb of one of Philip II’s seven wives, most likely Nicesipolis of Pherai. Upon excavation in 1977, exposure to atmospheric conditions caused rapid deterioration of the frescoes, resulting in plaster flaking and colors fading. This necessitated immediate conservation efforts that involved controlled reburial and chemical stabilization to preserve the murals.

Tomb of Philip II (Tomb II)

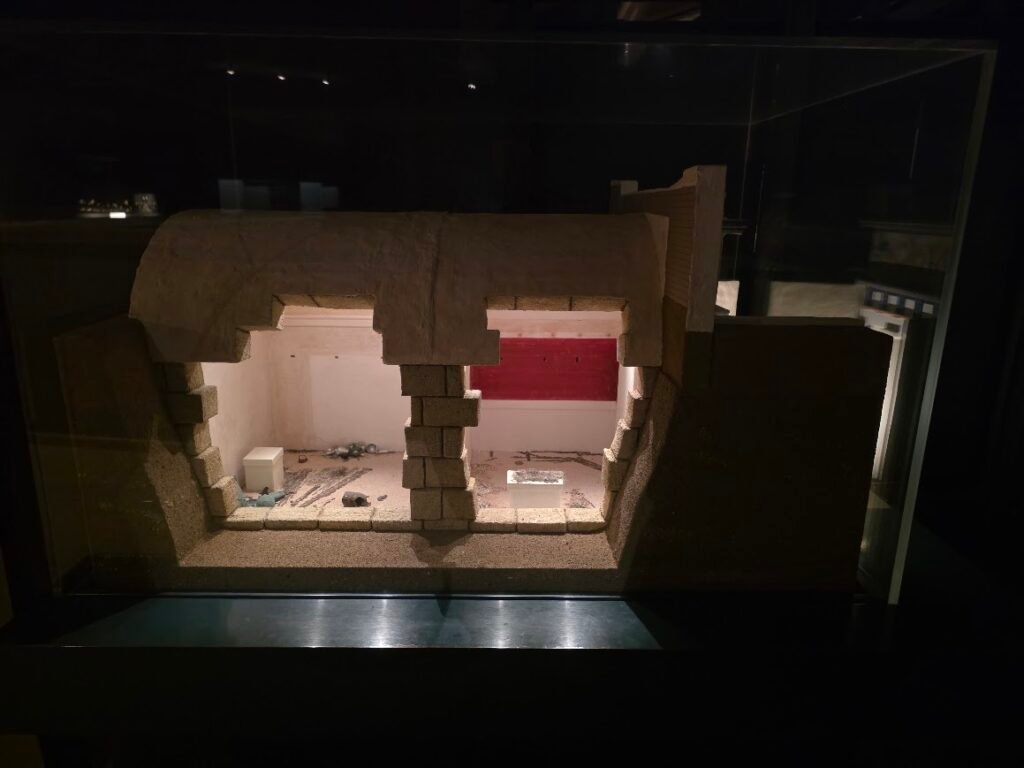

The Tomb of Philip II, referred to as Tomb II, stands as the stunning centerpiece of the Museum of Royal Tombs in Vergina, epitomizing the opulence of ancient Macedonian funerary traditions. Its layout reflects elite Macedonian burial practices, featuring a distinctive two-chamber design: a main burial chamber and a smaller antechamber. The main chamber held the cremated remains of Philip II (born 382 BCE—died 336 BCE), while the antechamber likely contained those of his royal wife, the Thracian princess Meda.

Sealed behind an impressive marble door and buried beneath a tumulus 110 meters in diameter and approximately 13 meters high, the tomb was preserved in remarkably low-oxygen conditions. This unique environment protected delicate organic materials—including wood and textiles—for more than two millennia. The structural ingenuity not only safeguarded the tomb’s contents but also thwarted ancient looters, allowing Tomb II to be discovered largely intact.

Visitors can descend to the site and admire the beautifully crafted Doric façade, an exquisite example of fourth-century BCE artistry. It features two friezes: a Doric frieze with triglyphs and metopes, and a taller Ionic frieze depicting a dramatic hunting scene—an iconography closely tied to Macedonian identity and royal authority.

Showcasing Celebrated Treasures from the Tomb of Philip II

Although visitors cannot enter the burial chambers of the Tomb of Philip II, the museum brings these spaces to life through an extraordinary selection of artifacts now on display. Together, they illuminate the lavish funerary rites of ancient Macedonians and the cultural world of its royal dynasty .

To appreciate these objects fully, it helps to understand the scale and ritual of Philip’s burial. Like the heroes of Homeric epic, Philip was cremated amid sumptuous offerings. The remains and objects from his funeral pyre —both sacred and ritually polluting—were gathered and deposited in the grave, which was then covered by a monumental tumulus of charred bricks, ash, and burned goods. Contemporary evidence suggests the pyre was a grand timber structure that echoed the size and splendor of the tomb itself. Reclining on a gold-and-ivory couch and clad in his panoply , the king was crowned with a golden oak wreath as he was delivered to the flames. Rich grave offerings, including dogs and horses, accompanied him; tradition records that one of his young wives, the Thracian princess Meda, joined him in death, reflecting the intense bonds of loyalty and dynasty.

The following highlights identify the museum’s principal displays from the royal tombs; photographic images and detailed captions follow in the next section.

- Gold Larnax of King Philip II: The world‑famous 24‑carat gold chest that once contained Philip’s cremated remains, decorated with the 16‑rayed Sun of Vergina; found inside a marble sarcophagus in the main chamber.

- Gold Larnax of Meda: A smaller gold larnax, likely belonging to Philip’s royal wife Meda, bearing a 12‑rayed sun emblem; recovered from a separate sarcophagus in the antechamber.

- Gold Oak Wreath of Philip II: The wreath recovered from the main larnax, comprising hundreds of leaves and acorns and surviving in substantial weight despite partial melting on the pyre.

- Gold Myrtle Wreath of Meda: The wreath placed on the antechamber couch and found within Meda’s larnax.

- Gold and Purple Fabric of Meda: The richly colored textile in which Meda’s bones were wrapped.

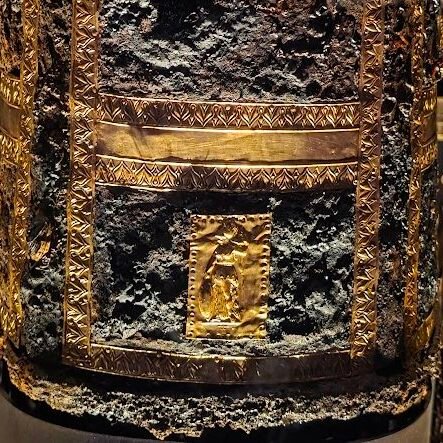

- Gold‑decorated Panoply of Philip II: The king’s iron and gold armor, the most complete classical panoply known, fitted to his frame and richly ornamented.

- Gold image of Athena (detail of the cuirass): The small gold icon sewn onto Philip’s cuirass, invoking divine protection .

- Gold and Ivory Shield of Philip II: A composite shield with gilt plates, ivory inlays, and an ivory‑gilt central group likely representing Achilles and Penthesileia .

- Weaponry of Philip II (336 BCE): The full assemblage of arms and armor recovered from the tomb, including swords, spears, greaves, and associated fittings.

- Weapons from the Main Chamber Threshold: The weapons and related gear found at the doorway to the main burial chamber, contextualizing the placement of grave goods.

- Vessels for the Bathing of the Dead: Cauldrons, bowls, jugs, and related implements used in lustral bathing rites and deposited with the king.

- Silver and Gold Diadem with the “Heracles knot”: A high‑status diadem combining precious metals and symbolic iconography.

- Banquet Utensils and Vessels: The exceptionally complete silver service intended for funerary feasting, illustrating elite dining ritual and craftsmanship.

- Gold‑and‑Ivory Couch from the Main Chamber: The spectacular couch with carved ivory and gold reliefs, including the hunting frieze and portrait heads .

- Remains of the Funerary Pyre: Archaeological evidence of the monumental pyre that accompanied Philip’s cremation and sealed his tomb.

Treasures from Philip II’s Tomb: Images and Captions

The Gold Larnax of Philip II is one of the most significant archaeological finds in Greek history and is the most admired display at the Museum of the Royal Tombs. This spectacular 4th-century BC ash-chest held his cremated remains and is made from thick sheets of hammered pure 24-karat gold, weighing approximately 8 kg (7,820 grams). Its lid is adorned with the 16-rayed Vergina Sun, a prominent symbol of the Macedonian royal family, along with two rosettes, the inner of which is filled with blue enamel. Relief palmettes and lotus buds frame five enameled rosettes on the sides, while the feet are embellished with rosettes and terminate in lion-paw designs. Inside the larnax lay the magnificent Gold Oak Wreath that crowned the deceased king. The wreath boasts 313 leaves and 68 acorns, with a surviving weight of 717 grams, having been partially melted in the pyre. It is the heaviest and most impressive wreath surviving from Greek antiquity and represents a remarkable achievement of a skilled goldsmith whose name remains unknown.. Polycentric Museum of Aigai / Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures — photo credit: Xpat.gr.

passing through the flames of the funeral pyre, continues to be the most beautiful classical Greek jewel that we know of discovered alongside her remains. In the background, golden roundels embossed with stars, from the antechamber of Philip’s tomb. Polycentric Museum of Aigai / Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures — photo credit: Xpat.gr.

The iron helmet showcases an embossed bust of the goddess Athena. The cuirass, a classic linen type reinforced with iron sheets and lined with leather, features elegant golden bands. The golden lion heads that fasten the cuirass serve not only as decorations but also as symbols of royal virtue.

The iron sword, trimmed with gold and paired with a wooden sheath adorned in ivory, reflects exquisite craftsmanship. The handle, or “apple,” is topped with a tiny golden helmet crowned by a sphinx. An embossed wild beast graces the cheek piece of the helmet, adding to the majestic aura of this remarkable artifact. Photo credit: Xpat.gr.

Weapons were to men what jewels were to women: valuable objects that served as partners in combat and symbols of status that accompanied the warrior and hunter to the grave. The Macedonians of Aigai traditionally placed two spears or javelins with their deceased, occasionally including a sword and, in rare cases for the exceptionally wealthy and eminent, a helmet. Nevertheless, during the burial of his father, Philip —the General-King who unified Macedonian rule and became the foremost general of all Greeks —Alexander the Great went above and beyond previous customs by offering the deceased four complete suits of armour: one for the funeral pyre and three as grave goods. These suits were crafted by skilled artisans who incorporated the latest advancements in metallurgy. Furthermore, the armour was trimmed with gold.

In addition to the weapons offered in the funeral pyre and the suits of armour designated for the antechamber and the main chamber, the following items were discovered in the tomb, as depicted in the accompanying image: a shield made of wood, leather, and cloth, reinforced with iron bands and adorned with embossed lions; a pectoral enhanced with an iron plate; an iron sword with a wooden sheath inlaid with ivory; two pairs of bronze greaves; an iron head of a sarissa; an iron spike used to anchor the spear into the ground; and nine iron spear and javelin heads, two of which were embellished with wide golden plates. Photo credit: Xpat.gr.

LEFT: A leather pectoral decorated with a gilded silver sheet; Two gold molten gorgoneia (Medusa heads), ornaments of a linen cuirass that had disintegrated; golden rosettes and chain links, elements that were used for the fastening and decoration of the linen cuirass.

MIDDLE: Double golden pin with sheath and chain; A gilded silver sheet that covered the front and the underside of a leather gorytos (Thraco-Scythian quiver). On the greater part of its surface are depicted scenes from the conquest of a city, probably that of Troy. In the upper right corner there is the image of a fully armed warrior that can possibly be the god of war, Ares; 75 bronze arrowheads; Gold ring-like plates that decorated the bow.

RIGHT: A pair of gilded bronze greaves. Photo credit: Xpat.gr.

knot” which the hero himself occasionally wore, as well as the bronze wine jug with a gorgon-shaped handle, which, together with the bronze patera (tray), served as the libation vessels necessary for the daily rituals performed by the King. The same is probably true for the torch. The few clay vessels found in the tomb—a wine jug, a perfume jar, and four salt-cellars —were, in all probability, the usual necessary objects for the funeral rites. Photo credit: Xpat.gr.

knot” of King Philip II, 350-336 BCE

This remarkable diadem features a silver cylinder adorned with incised lozenges that form a circle, secured by a cylinder embellished with a relief of the “Heracles knot.” Entirely gilded except for the central row of lozenges, it creates a striking bi-chrome effect reminiscent of woven textile cords. A unique homage to the girdle of Heracles, this diadem symbolizes the divine origin and high priestly status of the Macedonian Heracleid kings.

About The Funerary Pyre of Philip II:

According to ancient tradition, still alive in Aegai in the 4th century BCE, the dead king — together with the precious objects that had belonged to him in life — was consigned to a magnificent funerary pyre. The remains of the pyre were cast above the tomb, as was customary, presenting an image of splendour that alone would have sufficed to demonstrate that he stood above all others. On a platform of mud bricks smoothed with white mortar a monumental timber structure was erected which, judged by the iron nails and bronze fittings of its door, matched the tomb itself in size and luxury. Within this funerary house, reclining on an ornate gold-and-ivory couch and wearing his golden oak wreath, Philip was delivered to the flames. Thrown onto the pyre with him were weapons and garments, funerary wreaths, vessels of precious perfume, jars of oil and fruit; animals were also sacrificed — among them dogs and horses. After the burning, the king’s bones were carefully gathered, washed with wine, wrapped in purple cloth and placed, together with the wreath, in a golden larnax. The larnax was then secured inside a marble sarcophagus, the heavy door closed, and the tomb sealed for ever. Polycentric Museum of Aigai / Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures — photo credit: Xpat.gr.

Tomb of Alexander IV — “Tomb of the Prince” (Tomb III)

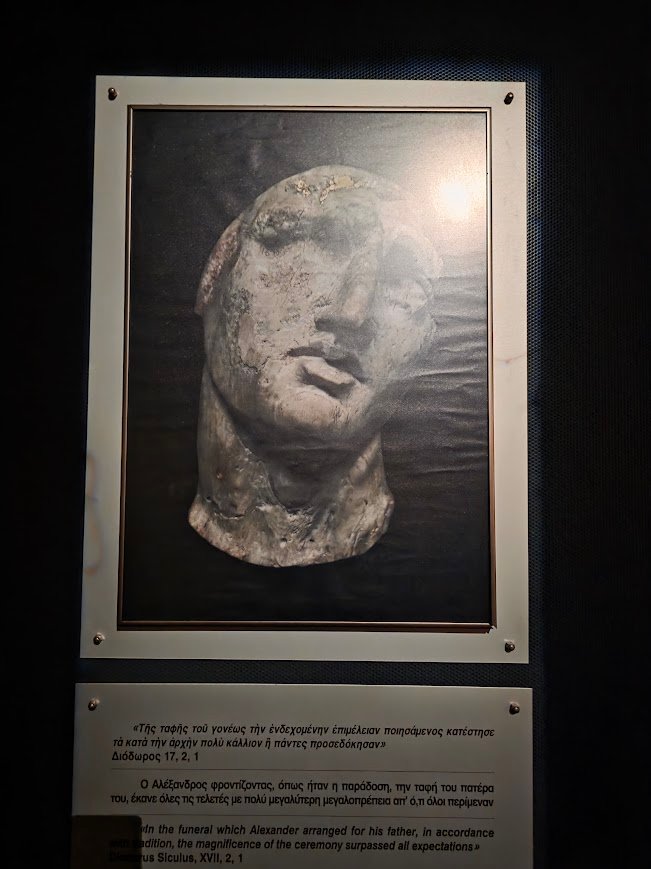

North‑west of Philip II’s tomb stands the so‑called Tomb of the Prince (c. 310–300 BCE), widely attributed to Alexander IV, the posthumous son of Alexander the Great and Roxane. Osteological analysis of the cremated remains—those of a youth of about 13–14 years —and the richness of the burial assemblage support this identification. Classical sources and later historians have long accused Cassander of responsibility for the prince’s premature death, a sombre backdrop to the site.

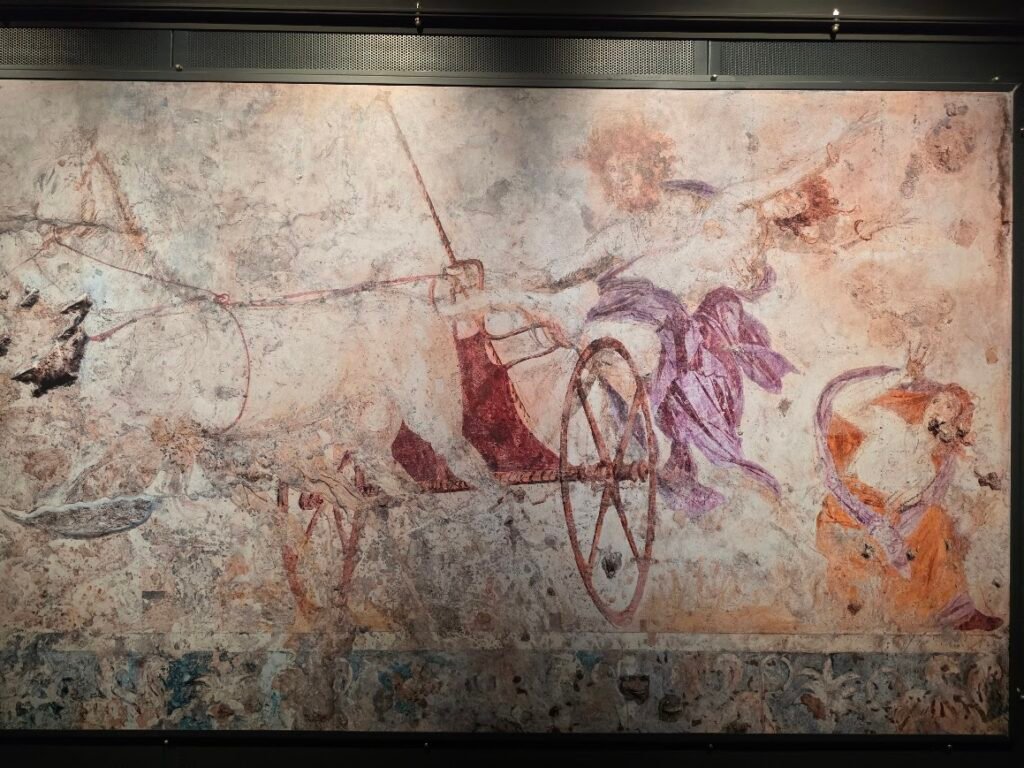

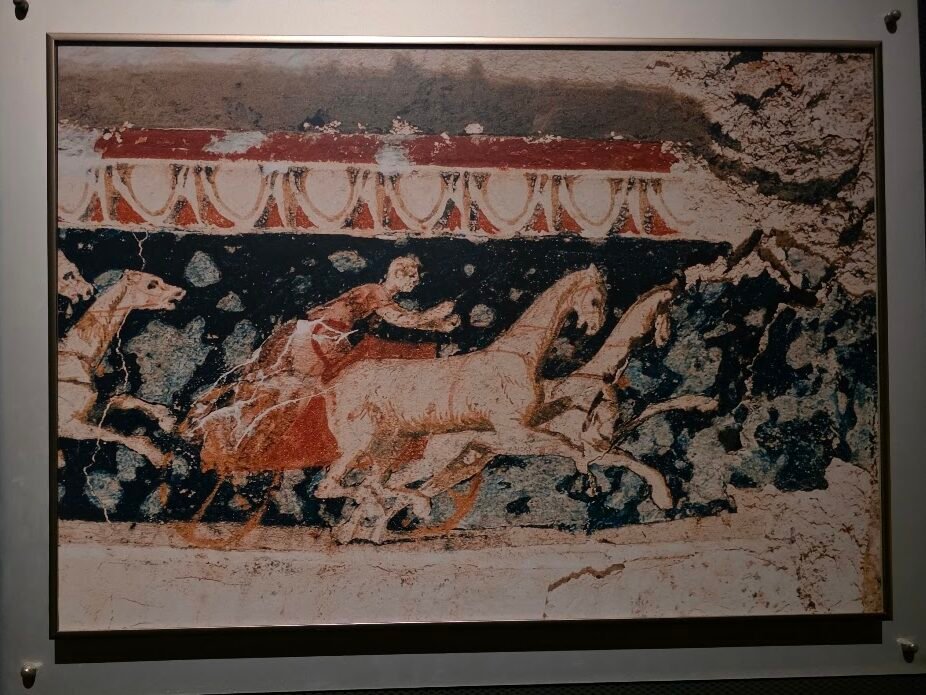

Architecturally the tomb echoes Philip’s vault on a reduced scale. Its stuccoed Doric façade once carried a painted frieze (now lost), and two relief shields beneath the frieze retain traces of their original decoration. Inside, the antechamber features a painted frieze of chariots; the burial chamber yielded a lavish array of gold and silver —chiefly banqueting vessels —alongside ivory objects , weapons, pottery and other grave goods. The cinerary urn is a silver hydria, its neck encircled by a gold oak wreath. A wooden mortuary couch richly inlaid with gold and ivory was also recovered; its decoration includes a striking scene of Dionysos accompanied by a flute‑player and a satyr.

Today the tomb’s finds are displayed in glass cabinets before the burial chamber, offering visitors an intimate encounter with the material culture of Macedonia’s royal house.

A young flute-playing satyr is leading Dionysos and his companion to revellery. Polycentric Museum of Aigai / Royal Tombs – Display of Treasures — photo credit: Xpat.gr.

2. Central Museum Building of Aigai

After exploring the Museum of the Royal Tombs, our journey continues to the new Central Museum Building, a destination in its own right. Opened in late 2022 and located 1.7 kilometres from the Royal Tombs, this contemporary space offers a strikingly different experience. Where the tombs are dimly lit and intimate, focused almost exclusively on kings and funerary ritual, the Central Museum Building feels open and almost weightless, flooded with natural light and expansive volumes of white stone. Here, the story of royalty is presented alongside the lives of the ordinary citizens who once filled the city, creating a richer, more complete picture of ancient Aigai.

The Central Museum Building serves as the unifying core of the Polycentric Museum of Aigai, which includes Philip II’s Palace and Theater, the vast necropolis of Aigai, and the Museum of the Royal Tombs. It acts as the symbolic gateway to the archaeological site, guiding visitors through the history of Aigai, the culture of the Macedonians, and the wider Hellenistic Oikoumenē (World), while also housing the physical headquarters of the digital museum “Alexander the Great: From Aigai to Oikoumenē.”

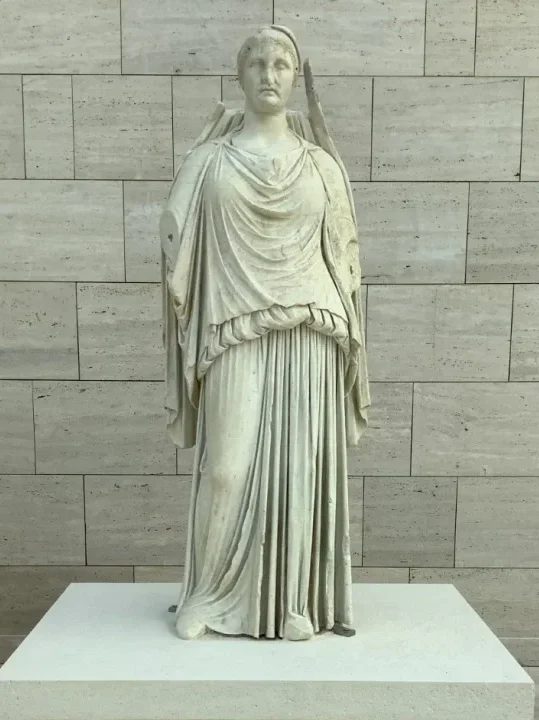

Alongside the introductory exhibition, “A Window to the World of Alexander the Great,” the building unfolds through a sequence of displays: an architectural exhibition centred on a reconstructed section of the palace, a sculpture exhibition, the core exhibition “Aigai Memory,” the temporary exhibition “Oikoumenē Antídoron,” and an Art Gallery featuring works by contemporary artists.

The main exhibition, “Aigai Memory,” brings the ancient city back into focus through what was broken, burned, or quietly abandoned. Fragments recovered from layers of destruction—everyday tools, weapons, symposium vessels, stamped roof tiles, and traces of women’s domestic lives, including jewelry, hairpins, makeup pots, and household keys—are woven into a narrative that reveals how life once unfolded in the Macedonian capital, from domestic routines to public ritual. The exhibition moves between the palace and the wider city, culminating in the remains of the monumental funeral pyres of the Temenids, where traces of power survive in ash, metal, and melted ornamentation. Its final galleries present nine richly adorned “Ladies of Aigai,” reconstructed with their full array of jewelry, underscoring the visibility, authority, and symbolic presence of elite women within the Macedonian royal world. Together, these objects transform absence into memory, allowing Aigai to be understood not as a ruin, but as a lived city

Many of the artifacts come from excavations carried out in recent years within the ancient city itself, and curators plan to regularly refresh the displays as new discoveries are made. With less than ten percent of Aigai excavated so far, the museum is not a conclusion, but an invitation—bringing an ancient city back into view, one fragment at a time.

Central Museum Building of Aigai: Images and Captions

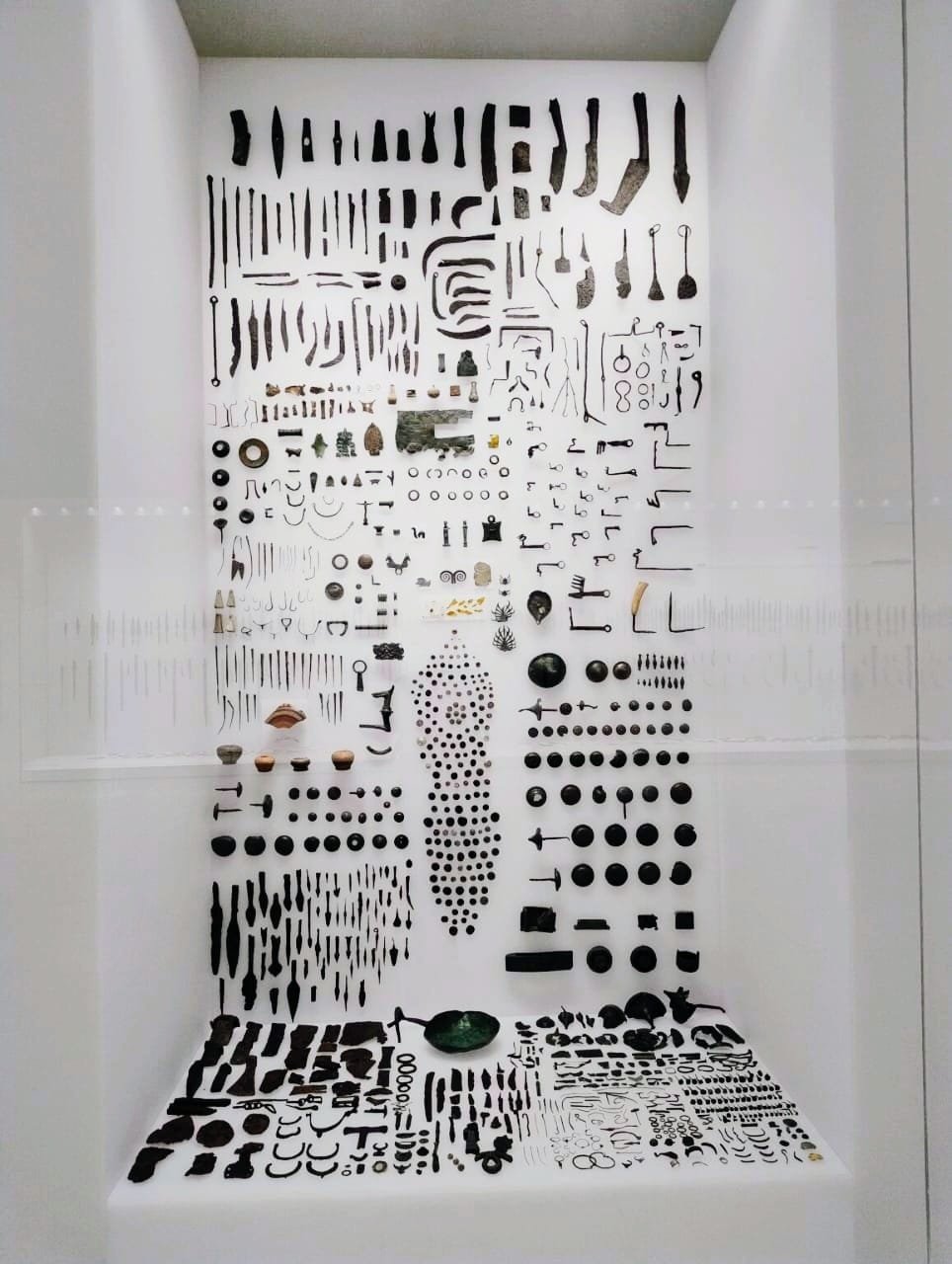

Arms and armour of the ancient Macedonians, arranged in chronological sequence. The display begins with long swords, spears, and javelins, while later periods—marked by the rise of cavalry warfare—show shorter swords. Knives, spear and javelin heads, helmets, shields, and the era’s ultimate weapon, the famed sarissa, reaching up to six metres in length, are also presented, with surviving fragments given pride of place. Polycentric Museum of Aigai /Central Museum Building — photo credit: Xpat.gr.

View of the exhibition: in the rear display cases on the right and left are heads of korai (maidens) and daemons (spirits). At the centre are remains from the monumental funeral pyres of the Temenids, including fragmented burial treasures and traces of royal power. From the background, nine Macedonian queens appear as if advancing toward the foreground. Polycentric Museum of Aigai /Central Museum Building — photo credit: Xpat.gr.

Key Takeaways

- Xpat.gr explores the rich history of Aigai, focusing on the Museum of the Royal Tombs and the New Central Museum Building.

- Visitors experience the grand displays of royal treasures, including the tomb of King Philip II, showcasing ancient Macedonian burial practices.

- The Central Museum Building offers insights into daily life and culture in ancient Aigai, contrasting with the solemnity of the royal tombs.

- The archaeological site of Aigai, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, features significant remains such as the palace, theatre, and numerous burial mounds.

- Aigai’s discoveries reveal a profound connection to Macedonia’s historical narrative, bridging the past with insightful museum presentations.